In the race to meaningfully integrate Artificial Intelligence into drug discovery, particularly in predicting toxicology, we often get seduced by high-scoring metrics. An AUC of 0.95! An F1 score of 0.88! These numbers look impressive on a training log, offering a comforting sense of rigour and progress. They suggest that a complex biological problem has been brought under control.

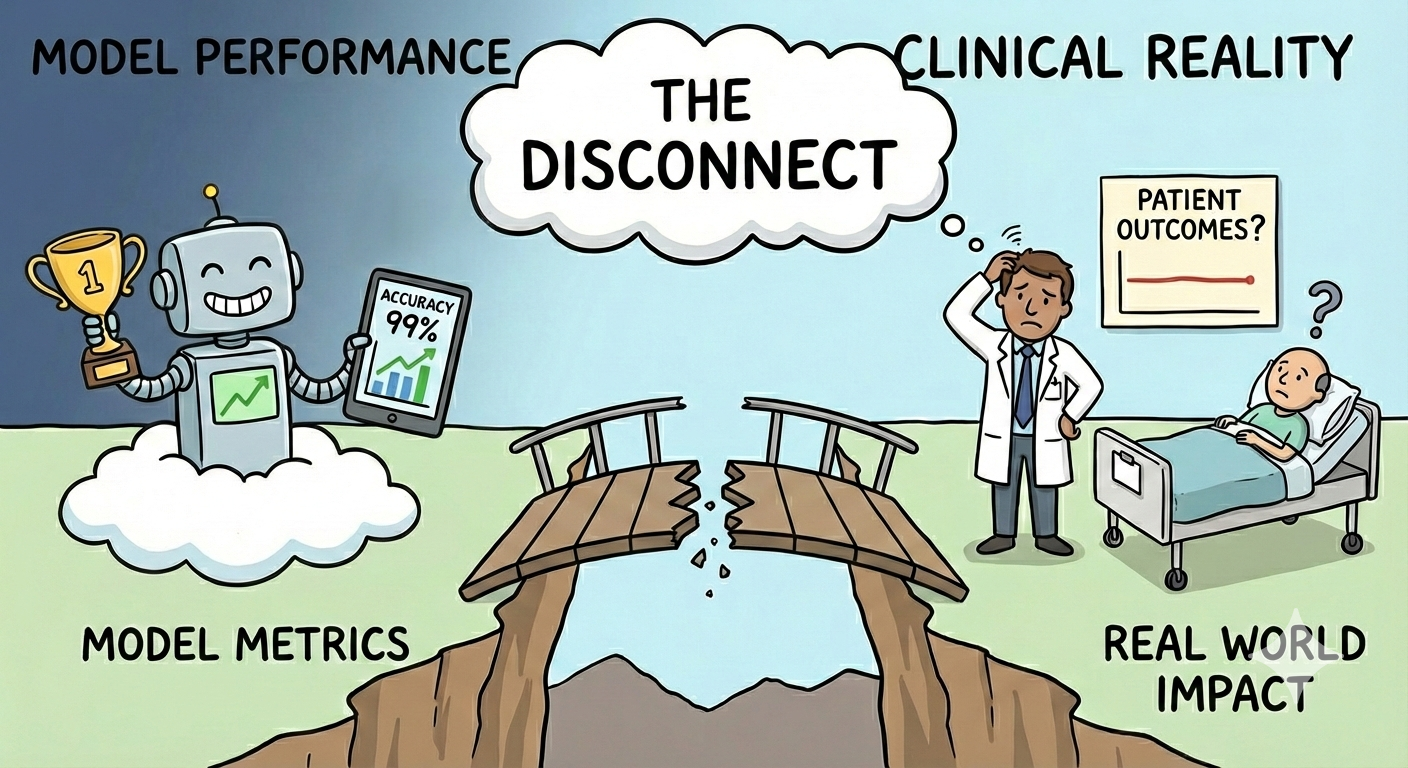

But let's face a sobering truth: Good metrics won't save lives.

When developing and validating AI models for predicting adverse drug reactions (ADRs), such as cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, or even common off-target effects, we need to look beyond optimising statistical performance. We need to ask whether these models can reliably support real decisions about compound progression, dosing, and patient safety.

Most validation metrics are derived from training and test sets that are small, carefully curated, and confined to narrow regions of chemical space. The impact of this is that strong performance often reflects familiarity with the dataset rather than robustness to novelty. These benchmarks rarely capture the biological and chemical uncertainty encountered in real drug development.

This has been discussed at length in the past few years, but recent work has focused on understanding exactly why these benchmarks don’t work, enabling the development of better and more rigorous benchmarks (see: OpenADMET). Pat Walters recently posted a visual demonstration as to why a common benchmark used for virtual screening (DUD-E), is flawed when used to validate machine learning models. The decoys (inactives) simply look different from the true actives, and that’s the pattern the model - a glorified pattern matcher - will learn, rather than the underlying physics behind drug-protein binding.

Other findings from groups like Leash Bio demonstrate that models learn other surprising patterns, such as the chemist who designed the compound.

The core problem lies in the disconnect between the in silico world and biological reality..

Taken together, these limitations help explain why strong benchmark performance so often fails to translate into reliable real-world predictions. We are increasingly aware that many current validation approaches are insufficient, and we are beginning to understand why.

The next question, then, is practical. If existing benchmarks fall short, how can we evaluate our models in ways that better reflect the decisions they are meant to support?

At Ignota Labs, we don't focus our attention on how well our models can predict for a small set of molecules in a limited chemical space. We care about one thing: How well can this model be used to save lives, by understanding adverse events and accelerating the delivery of safer medicines?

To bridge this gap, we must move toward more practical, rigorous, and clinically relevant use cases for AI toxicology models. Instead of resting on internal validation metrics, demand evidence of external, consequential validation.

Here are examples of how AI toxicology models can be validated with a focus on real-world impact:

Human biology doesn't care about your F1 score. Until our validation frameworks account for the 90% failure rate in clinical transitions, and the fact that over 80% of genomic data used in drug discovery still comes from populations of European descent, leaving massive gaps in safety for the rest of the world, AI will remain a peripheral tool. Until industry benchmarks reflect the "messy" reality of global biology and the high-stakes environment of clinical trials, we aren't revolutionising drug safety—we're just refining the status quo.

At Ignota Labs, we are trading statistical comfort for clinical accountability. A model's value isn't an arbitrary decimal point in a report; it's the measurable reduction of late-stage attrition. It’s the number of potential tragedies intercepted before a molecule ever touches a patient.

Author: Dr Layla Hosseini-Gerami