Everybody in the sector understands that most drug programmes fail at some stage. It is so widely accepted that it is built into portfolio strategy, financial modelling and investment theses. Failure is not surprising. It is expected.

What is talked about far less is what should happen after a programme fails. What is the right next step? What can we learn, and how should that learning be carried forward to continuously improve as an industry?

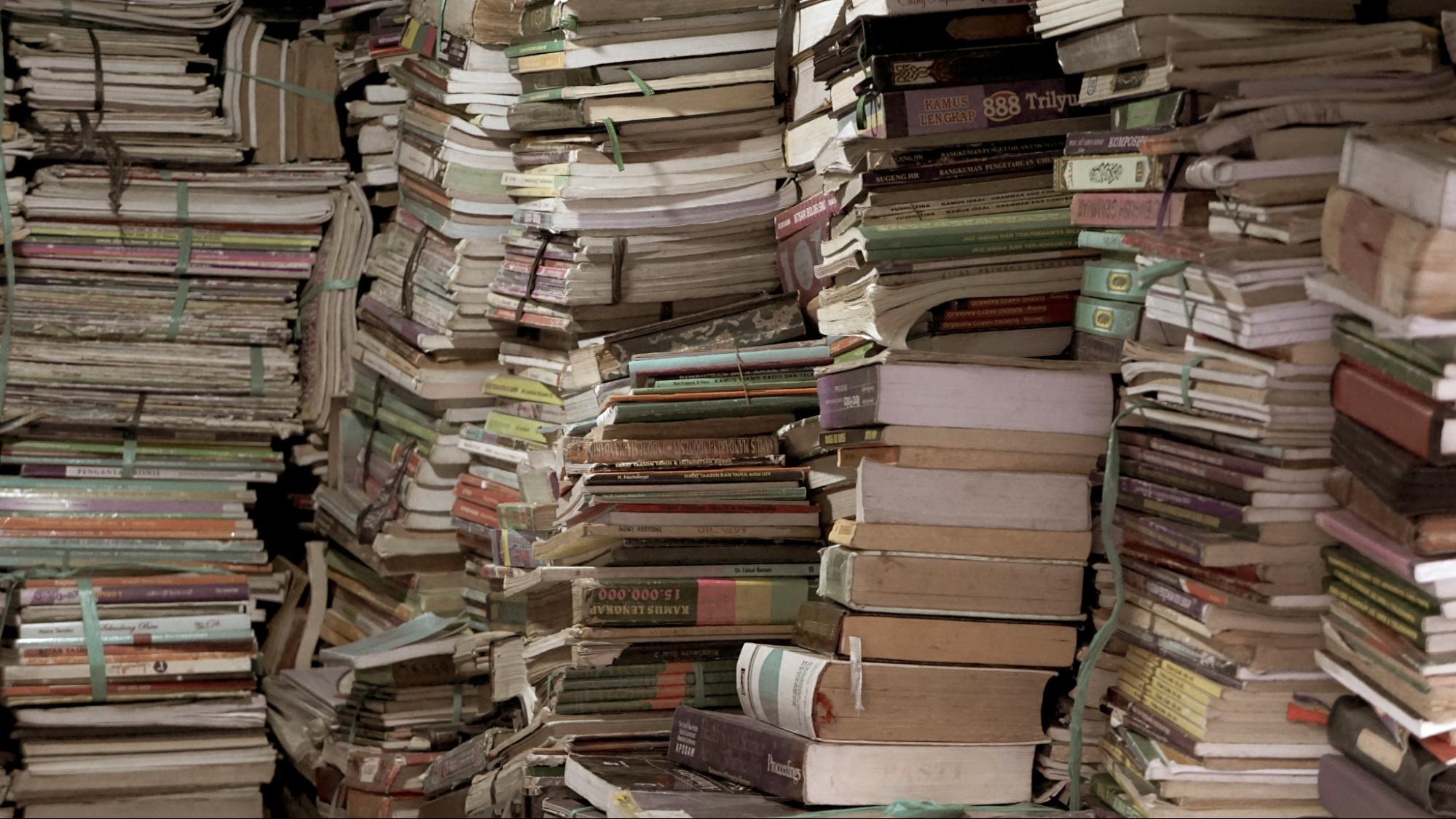

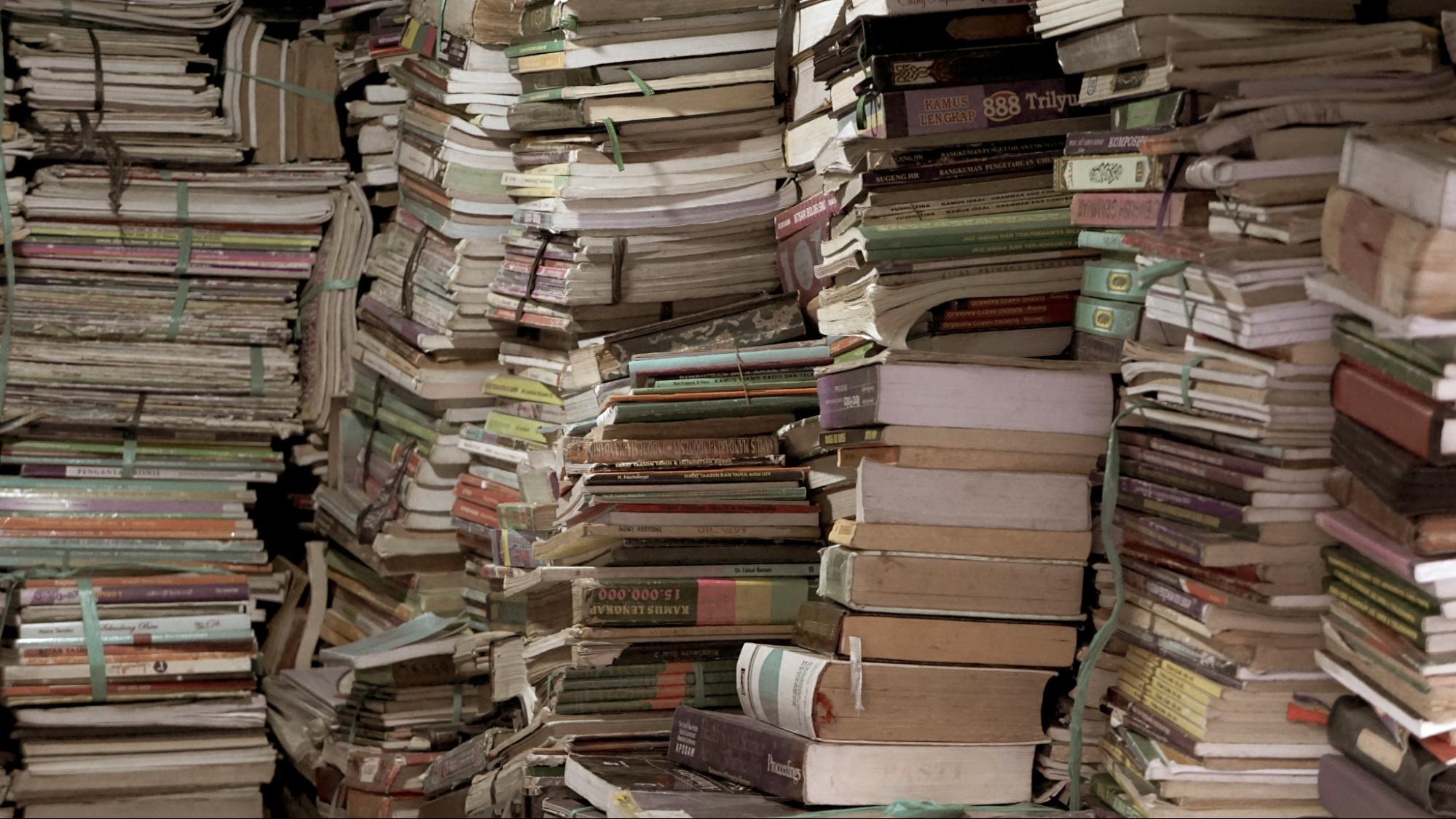

Right now, that doesn’t happen. When drug programmes run into trouble, the hard-won knowledge created over years is often lost almost immediately.

When a drug is developed, huge amounts of information are generated: clinical data, exploratory analyses, commercial assumptions, hypotheses that were ruled out, hypotheses that were not, regulatory feedback and years of tacit knowledge inside teams. Even when a programme fails, that information is incredibly valuable.

Yet when investors lose confidence and the project is shelved, all of that accumulated knowledge effectively vanishes.

A few years later, another company often launches a project going after the same target or disease and repeats the same mistakes, frequently without knowing anything about what happened the first time.

This happens again and again. It is hugely inefficient, costs a fortune, and it slows the entire sector down.

Many drug programmes do not fail because the idea was fundamentally wrong. They fail because something unexpected happened and the team did not have the right tools or time to understand why - or importantly, what is the route cause of the issue, and can it be resolved.

Drug safety is a good example. 56% of drugs fail due to safety issues. Clinical data might tell you that patients experienced chest pain, raised liver enzymes or neurological symptoms, but these are medical descriptions rather than biological explanations. There can be hundreds of possible mechanisms behind each signal. Traditional investigative toxicology can take years and is rarely invested into outside big pharma (even then, it is used sparingly). Most companies cannot afford to spend that long on a single question where the answer might not be actionable.

The consequence is a predictable decision. The programme is paused or cancelled. Investors redirect their attention. Companies often close down. The knowledge is lost. But failure often contains exactly the information needed to succeed the second time.

In drug discovery, distressed assets rarely move to the teams best placed to understand and fix them. Instead, promising programmes are often shelved or fragmented across portfolios once they hit a setback. Without a mechanism to bring this knowledge back together, the same classes of drugs run into the same issues every few years. The sector keeps relearning the same lessons.

We believe this is where a drug turnaround model becomes essential. The knowledge created during development should not be lost. It should be captured, analysed and built on.

There is a strong bias in the market that anything with a history of issues should be written off. The logic is understandable. Investors have limited time and many opportunities to evaluate. A clean story is easier to fund than a complex one.

But this mindset leaves a lot of value on the table. Many failures are not terminal, they are simply misunderstood. Some safety issues are solvable once the mechanism of toxicity is known. Some programmes were on the right track but did not have the resources or the tools to diagnose the problem.

Investors will eventually need to move from thinking “this failed, so it has no value” to thinking “this failed, so the most valuable information already exists”. That psychological shift will unlock opportunities that are currently ignored.

A common objection is that old programmes are not worth revisiting because the patent clock has already run down. In practice, this is often not the case. When a drug is re-engineered to overcome a known clinical issue, that work results in a new chemical entity. If the new structure sits outside the original claims, it can be protected by fresh patents, which resets the clock and gives full exclusivity on the improved compound.

Even when the solution does not require a new structure, there are other routes to new intellectual property. Reformulations, new salt forms, new polymorphs or new methods of use can each be the basis for fresh IP protection. These options do not offer protection as strong as composition of matter, but they can still extend commercial life materially and give developers the runway needed to bring an improved or more targeted version of the drug back into the clinic.

In other words, IP is rarely a definitive barrier and should not be used as a blanket excuse for not looking again at these programmes. If a programme contains real scientific value, there is usually a viable path to protect it.

At Ignota Labs, we build on the failings of previous projects to increase our odds of success. By understanding why past attempts fell short, we are able to move faster and more cost effectively to key clinical inflection points. Our SAFEPATH platform helps us understand why a drug behaved the way it did. We map off-target binding, chart the biological pathways involved and recreate the problem in controlled systems. Once we understand the mechanism, we can evaluate whether the issue can be resolved. We believe that around 10 to 20% of failed drugs fall into that category. Applied across the industry this is potentially hundreds of billions of dollars in value.

The surprising truth is that most of these programmes were 80 to 90% of the way to success before they were abandoned. With the right insight and a focused approach, many of them can be brought back into the clinic quickly and with a greater probability of success.

This is also how the most durable companies in the industry have succeeded. Their progress did not come from one breakthrough but from compounding knowledge. Every miss refined their priors, strengthened their platform and increased the odds of success the next time.

The entire industry can operate this way if we stop losing what we learn.

Author: Sam Windsor